(c) Rabbi Menachem Creditor

Dearest Friends,

[I share these words with you from a distance, as the Jewish obligation to seek the welfare of one’s fellow citizens, coupled with the American civic duty to serve on a jury of one’s peers (as I am called to do this week), compel my absence from our meeting. I am grateful to AJWS Board Chair Kathleen Levin for sharing my words with her voice.]

As we continue our journey as a Jewish organization fighting to end poverty and promote human dignity around the world, every moment is urgent. As the great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel famously taught, there is simply “no time for neutrality.” Every act is needed. Every gift, every word, every choice has the potential to save a life.

AJWS models this lesson well as a participant on the ground in many vulnerable parts of the world, where disasters and injustice collaborate to threaten not only the dignity but also the very lives of so many.

The thoughtful methods we employ to guide our work to end poverty and to promote human rights are only matched in their intensity by the relationships we create on the ground with our partners, channeling the biblical mandate to love our neighbors as ourselves (Lev. 19) by ourselves becoming neighbors with our global partners. We are not sending advice from far away. We are there, listening, collaborating, and marshaling our resources in service of our neighbors.

Most recently, thanks to the work and reporting from AJWS’s Director of Disaster Response & International Operations, Samantha Wolthuis, and Associate Director of Risk Management and Administrative Services, Aaron Acharya, who were on the ground in Nepal in the aftermath of the earthquakes just last month, we have been reminded well that the relational commitments we make - and the additional ones we ache for the capacity to make - save lives, each of which, Jewish tradition reminds us, is an entire universe (MIshnah Sanhedrin 4:5).

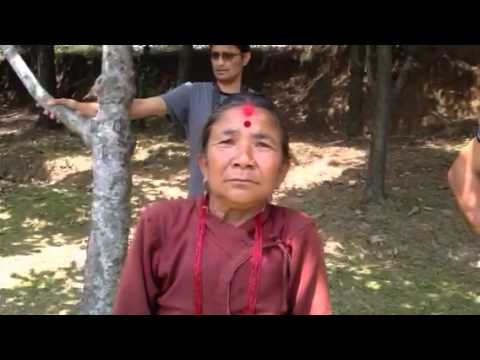

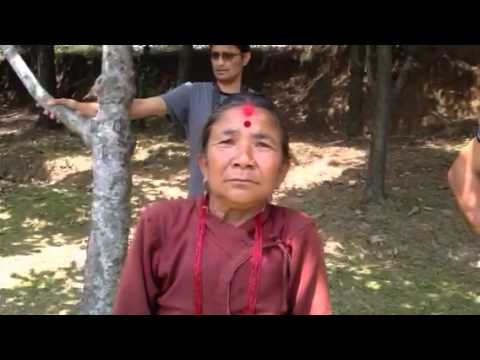

In Sam and Aaron’s second report, they shared the story of Saili Tamang, who lives in a village just west of Kathmandu. Her house was flattened by the quakes. She was denied assistance by the Nepalese government and army, whose use of “village development committees (VDCs)” meant that family and friends of the government officials are typically prioritized over Dalit and indigenous communities. We believe, as AJWS, that community members are best placed to serve their own communities in times of need. This past week’s Torah portion from the Book of BeMidbar, Numbers, gives biblical language for the basis of that approach: “There shall be one law for you, whether stranger or citizen of the country. (Num. 9:14)”

Whether it is disaster relief, grassroots work to further the dignity and rights of LGBT people around the world, 84 visits with lawmakers and officials on Capitol Hill, demanding an end to child marriage and violence against women and girls - in each of these urgent efforts we channel righteous indignation and commit to act, to seek one law for all people, every one of whom is created BeTzelem Elohim, in the Divine Image.

Just a few verses earlier than the one I just shared, we read that one who has the ability to fulfill their sacred obligation - and does not - cuts themselves off from their people (Num. 9:13). This means one very clear and profound thing: We are called by Jewish tradition to do everything we possibly can to recognize the dignity in all people, to listen well to the wisdom of others, for the Image of God is not only what we see when we look in the mirror. As we learn:

Dearest Friends,

[I share these words with you from a distance, as the Jewish obligation to seek the welfare of one’s fellow citizens, coupled with the American civic duty to serve on a jury of one’s peers (as I am called to do this week), compel my absence from our meeting. I am grateful to AJWS Board Chair Kathleen Levin for sharing my words with her voice.]

As we continue our journey as a Jewish organization fighting to end poverty and promote human dignity around the world, every moment is urgent. As the great Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel famously taught, there is simply “no time for neutrality.” Every act is needed. Every gift, every word, every choice has the potential to save a life.

AJWS models this lesson well as a participant on the ground in many vulnerable parts of the world, where disasters and injustice collaborate to threaten not only the dignity but also the very lives of so many.

The thoughtful methods we employ to guide our work to end poverty and to promote human rights are only matched in their intensity by the relationships we create on the ground with our partners, channeling the biblical mandate to love our neighbors as ourselves (Lev. 19) by ourselves becoming neighbors with our global partners. We are not sending advice from far away. We are there, listening, collaborating, and marshaling our resources in service of our neighbors.

Most recently, thanks to the work and reporting from AJWS’s Director of Disaster Response & International Operations, Samantha Wolthuis, and Associate Director of Risk Management and Administrative Services, Aaron Acharya, who were on the ground in Nepal in the aftermath of the earthquakes just last month, we have been reminded well that the relational commitments we make - and the additional ones we ache for the capacity to make - save lives, each of which, Jewish tradition reminds us, is an entire universe (MIshnah Sanhedrin 4:5).

In Sam and Aaron’s second report, they shared the story of Saili Tamang, who lives in a village just west of Kathmandu. Her house was flattened by the quakes. She was denied assistance by the Nepalese government and army, whose use of “village development committees (VDCs)” meant that family and friends of the government officials are typically prioritized over Dalit and indigenous communities. We believe, as AJWS, that community members are best placed to serve their own communities in times of need. This past week’s Torah portion from the Book of BeMidbar, Numbers, gives biblical language for the basis of that approach: “There shall be one law for you, whether stranger or citizen of the country. (Num. 9:14)”

Whether it is disaster relief, grassroots work to further the dignity and rights of LGBT people around the world, 84 visits with lawmakers and officials on Capitol Hill, demanding an end to child marriage and violence against women and girls - in each of these urgent efforts we channel righteous indignation and commit to act, to seek one law for all people, every one of whom is created BeTzelem Elohim, in the Divine Image.

Just a few verses earlier than the one I just shared, we read that one who has the ability to fulfill their sacred obligation - and does not - cuts themselves off from their people (Num. 9:13). This means one very clear and profound thing: We are called by Jewish tradition to do everything we possibly can to recognize the dignity in all people, to listen well to the wisdom of others, for the Image of God is not only what we see when we look in the mirror. As we learn:

“[When a person] stamps out many coins with one mold, they are all alike. [But when God impresses the Divine Image into a human being,] not one of them is like his or her fellow. (Mishnah Sanhedrin 4:5)”

We know that precisely by noticing the difference between a mirror and a window we can be better Jewish activists. Staring at a mirror is a poor way to be in the world. We do not wish to be cut off from our people, from our neighbors, and so we choose to see the world through the clear lens (an ‘aspaklaria,’ in Talmudic aramaic), which both demands and brings in so much more light. That is the work of AJWS: we illuminate our fragile world by helping others to reveal their own brilliant and unique lights.

******

I recently came across a delightfully radical text from the Talmud. In it, the rabbis envision God praying. Leave behind the question of whether or not there is a God, and if there is, what that God might be like. That’s much less important than what we might discern from the WAY God is imagined by the ancient rabbis. If we truly listen to what they hoped God would pray for, I believe we might also hear echoes of what our own aching hearts - in this moment - wish for our world today, what we carry with us in our work with AJWS:

I recently came across a delightfully radical text from the Talmud. In it, the rabbis envision God praying. Leave behind the question of whether or not there is a God, and if there is, what that God might be like. That’s much less important than what we might discern from the WAY God is imagined by the ancient rabbis. If we truly listen to what they hoped God would pray for, I believe we might also hear echoes of what our own aching hearts - in this moment - wish for our world today, what we carry with us in our work with AJWS:

[The rabbis ask:] What does God pray for? Rabbi Zutra ben Tobi said in the name of Rab: “God prays: 'May it be My will that My mercy conquer My anger, that My mercy wash over My stricter qualities, so that I might behave with My children mercifully and see beyond the letter of the law.’” (Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot, 7a, adapted)

Try to leave behind any skepticism you might have. Be in the story for just this moment. Rabbi Zutra is suggesting that, just like a person, God has conflicting impulses, anger and mercy, and that there are rules even God feels compelled to follow, rules God would choose to violate out of kindness and concern for humanity. That’s radical enough, but immediately following Rabbi Zutra’s concept of God’s own prayer, we read the following:

It was taught: Rabbi Ishmael ben Elisha said: “I once entered into the Holy of Holies and saw God, seated upon a high and exalted throne. God said to me: ‘Ishmael, My child, bless Me!’ I replied: 'May it be Your will that Your mercy conquer Your anger, that Your mercy wash over Your stricter qualities, so that You might behave with Your children mercifully and see beyond the letter of the law.’ And God nodded to me. Here we learn that the blessing of an ordinary person must not be considered lightly in your eyes. (Babylonian Talmud, Tractate Berachot, 7a, adapted)

The difference between the first telling and second is not the prayer itself, as they are identitcal in both versions of the story. Rather, the difference is in who is the one offering the prayer. Notice that, in this second telling, God asks for a blessing and Rabbi Ishmael offers the prayer. This is a God who needs human partners, a God of deep caring, a God whose concern for mercy extends beyond what laws can describe.

Perhaps the deepest teaching in this text is this: It matters not if you believe in God; in the eyes of a person of faith, you are inescapably holy and worthy of concern.

For some in the world, help feels far away, something someone else does, perhaps even something God does. But AJWS’s approach is closer to the Talmud’s second telling, where even God’s holy concerns require human enactment. We are, as Heschel taught us, “images of God, a fraction of God’s power at our disposal.”

Perhaps the deepest teaching in this text is this: It matters not if you believe in God; in the eyes of a person of faith, you are inescapably holy and worthy of concern.

For some in the world, help feels far away, something someone else does, perhaps even something God does. But AJWS’s approach is closer to the Talmud’s second telling, where even God’s holy concerns require human enactment. We are, as Heschel taught us, “images of God, a fraction of God’s power at our disposal.”

Friends, the ‘Divine nod’ at the very end of the text means that when we work well and apply our best wisdom to addressing the needs of others, when we push our country’s laws to extend mercy and justice around the globe, when we push ourselves to succeed at these immense and urgent tasks, we are ourselves the very fulfillment of God’s own prayer.

May this world and all its inhabitants be blessed because we, as the leaders of American Jewish World Service, continue to be students of the tradition which both inspired our organization’s birth and illuminates its trajectory into the future.

Amen.